You might recall that I recently called out New York Times's Op-Ed writer Joe Nocera. This pertained to his foolish reasoning that the presence of a small watch maker in Detroit signaled some great come back for that city. Perhaps I was too hard on Nocera. It looks like he nailed the Harper Lee situation. He had the courage to describe frankly what those around Harper Lee did to her when the published the first draft of To Kill A Mockingbird as a new novel. In pertinent part, Nocera observed:

So perhaps it’s not too late after all to point out that the publication of “Go Set a Watchman” constitutes one of the epic money grabs in the modern history of American publishing.

Atta boy, Joe. Keep calling them like you see them. Maybe there is hope for you after all.

Nocera's Gem

Tuesday, July 28, 2015

Wednesday, July 15, 2015

I Wish I Had Said That

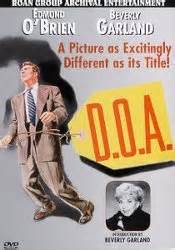

I signed up for an online course in film noir put on my Turner Classic Movies (TCM). As part of the process, they email me a film clip each day. Accompanying the clip is a discussion of the movie. The other day the film was DOA starring Edmund O'Brien. The clip was curated by a fellow named Richard Edwards. His take on DOA involved a general break down in order as chaos increased. He wrote:

As Robert Porfirio mentions in his article on Existential motifs, in a film like D.O.A.

we find ourselves in a meaningless, purposeless and absurd world. The threat of imminent death hangs over this film. While we (and the film's staging and camerawork) are constantly on the move, we have no certainty of our destinations. Walking into Los Angeles's police department, as Frank Bigelow (Edmund O'Brien) does at the beginning of this film, might be less of a quest for solutions and justice than a moment of resignation to the inevitable. The police station seems less of a place of security and more like a bureaucratic way station with long dimly lit corridors. We are beginning to find ourselves, over and over again, at the end of the line in the 1950s. Nowhere is this more clearly illustrated than in the plight of Frank Bigelow. As in the other Daily Doses this week, we (as well as audiences of that time) still want to hold the belief that there is somebody in charge of this decaying and violent world, but "a sense of malaise" and dread has now spread and doesn't seem containable. We can longer be certain that the police, or detectives, or ordinary people can hold back the anxiety and paranoia of the 1950s

When I read that description, I thought: Exactly. That is precisely what I have been trying to convey in all the Hofmann/Garvin novels (indeed, all my novels.) The two detectives spend their days trying to make sense out of a senseless world. Without intending to do so, they are on the front line of the battle against entropy, the last hope for order. Think of the novel Heroes in this setting and compare it to the classic hero's quest. Think of Smoke, where the arson fires get more and more complicated that they cannot be anything short of supernatural. Against such a destructive force, we send out two men, two ordinary men who try to make sense of it all.

Sadly, it looks like Robert Porfirio's 1976 essay No Way Out: Existential Motifs in the Film Noir,” is not readily available, Too bad: sounds like a great read.

As Robert Porfirio mentions in his article on Existential motifs, in a film like D.O.A.

we find ourselves in a meaningless, purposeless and absurd world. The threat of imminent death hangs over this film. While we (and the film's staging and camerawork) are constantly on the move, we have no certainty of our destinations. Walking into Los Angeles's police department, as Frank Bigelow (Edmund O'Brien) does at the beginning of this film, might be less of a quest for solutions and justice than a moment of resignation to the inevitable. The police station seems less of a place of security and more like a bureaucratic way station with long dimly lit corridors. We are beginning to find ourselves, over and over again, at the end of the line in the 1950s. Nowhere is this more clearly illustrated than in the plight of Frank Bigelow. As in the other Daily Doses this week, we (as well as audiences of that time) still want to hold the belief that there is somebody in charge of this decaying and violent world, but "a sense of malaise" and dread has now spread and doesn't seem containable. We can longer be certain that the police, or detectives, or ordinary people can hold back the anxiety and paranoia of the 1950s

When I read that description, I thought: Exactly. That is precisely what I have been trying to convey in all the Hofmann/Garvin novels (indeed, all my novels.) The two detectives spend their days trying to make sense out of a senseless world. Without intending to do so, they are on the front line of the battle against entropy, the last hope for order. Think of the novel Heroes in this setting and compare it to the classic hero's quest. Think of Smoke, where the arson fires get more and more complicated that they cannot be anything short of supernatural. Against such a destructive force, we send out two men, two ordinary men who try to make sense of it all.

Sadly, it looks like Robert Porfirio's 1976 essay No Way Out: Existential Motifs in the Film Noir,” is not readily available, Too bad: sounds like a great read.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)